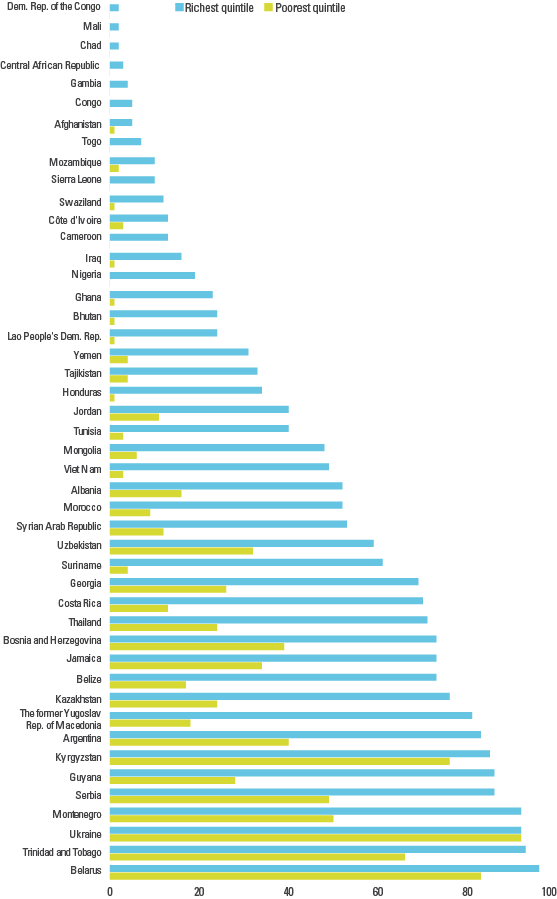

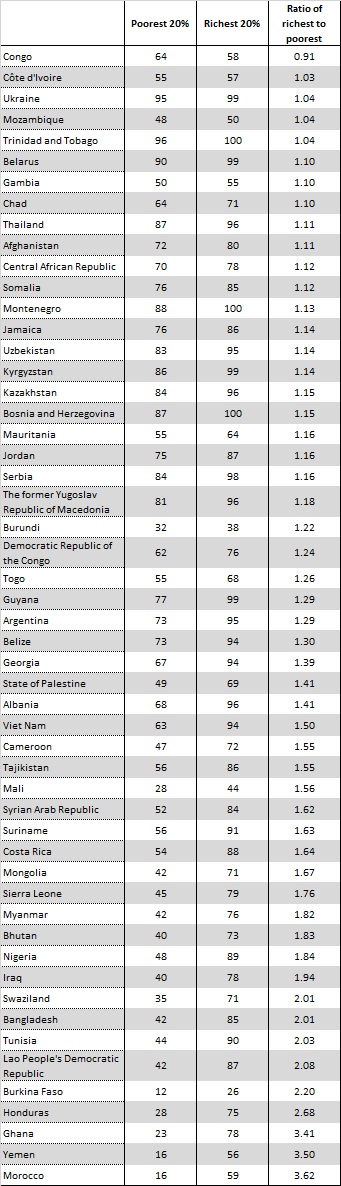

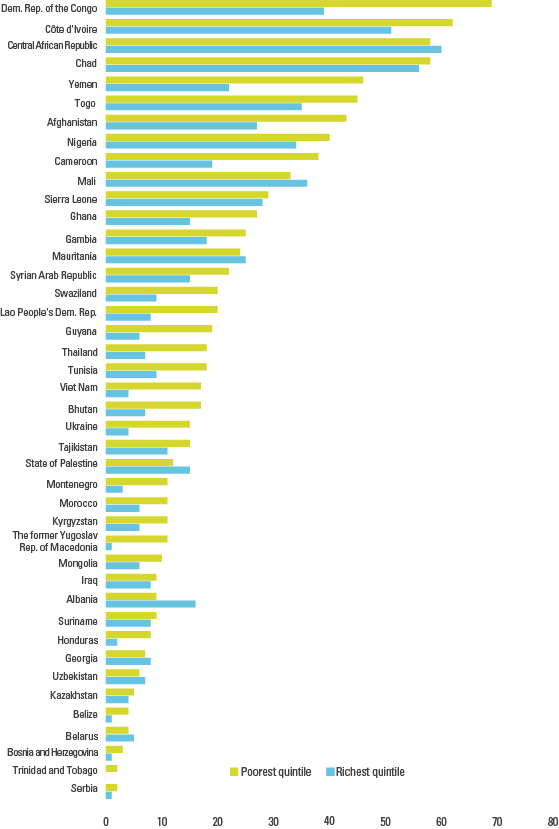

A young child’s home environment plays a key role in determining his or her chances for survival and development.[1] Optimal conditions include a safe and well-organized physical environment, opportunities for children to play, explore and discover, and the presence of developmentally appropriate objects, toys and books.[2] Several research studies suggest that children who grow up in households where books are available receive, on average, three more years of schooling than children from homes with no books. This finding holds regardless of a caregiver’s level of education, occupation or class and applies to rich and poor countries alike.[3] However, in three key indicators of a supportive early learning environment at home, children from the richest 20 per cent of the population fared far better than children in the poorest quintile.

DATA SOURCES

Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) are the main sources for nationally representative and comparable data on early childhood development. Some Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and other national household surveys have also collected information on early childhood development, typically with the standard, or modified, versions of the MICS questionnaire.

MAIN INDICATORS

Beginning with the fourth round of MICS (MICS4), the early childhood development indicators were consolidated into a single early childhood development module included in the questionnaire for children under 5 years of age.[8] The module is administered to mothers or primary caregivers of children under the age of 5 (0 to 59 months). Nearly all countries participating in MICS4 have collected the early childhood development module.

Early childhood development indicators capture the availability/variety of learning materials in the home, adult and paternal support for learning and school readiness, and non-adult care. Learning materials include both books and play materials defined as household objects, objects found outside (such as sticks, rocks, shells, etc.), home-made toys and manufactured toys. Activities that promote learning and school readiness include: reading books to the child; telling stories to the child; singing songs to the child; taking the child outside the home; playing with the child; and naming, counting or drawing things with the child.

Learning materials:

- Percentage of children under 5 who have three or more children’s books.

- Percentage of children under 5 with two or more playthings.

Support for learning:

- Percentage of children aged 36─59 months with whom an adult has engaged in four or more activities to promote learning and school readiness in the past three days.

- Percentage of children aged 36—59 months whose father has engaged in one or more activities to promote learning and school readiness in the past three days.

Inadequate care:

- Percentage of children under 5 left alone or in the care of another child younger than 10 years of age for more than one hour at least once in the past week.

MICS MODULE ON EARLY CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENT

MICS surveys have a standardized modules on early childhood development.

Download the MICS module on early childhood development (PDF)

[8] Indicator definitions in the third round of MICS (MICS3) differed for some early childhood development indicators. For example, the age group for the two indicators on support for learning (adult and father’s engagement) was children under age 5. As such, data on some of the indicators from MICS3 are not directly comparable with data collected in subsequent rounds of MICS for any given country.