Pneumonia remains the leading infectious cause of death among children under-five, killing nearly 2,600 children a day. Pneumonia accounts for 15 per cent of all under-five deaths and killed about 940,000 children in 2013. Most of its victims were less than 2 years old.

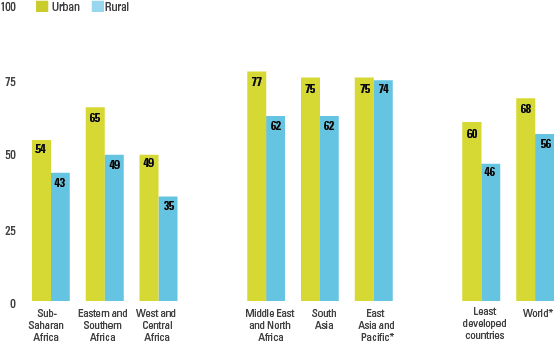

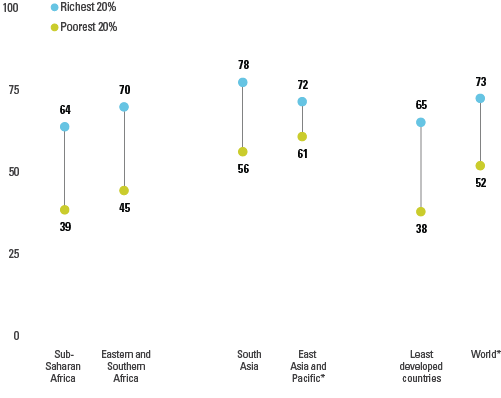

Pneumonia, along with diarrhoea, is a disease of the poor. 70 per cent of deaths attributable to these two diseases occur in just 15 countries, all of which are in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

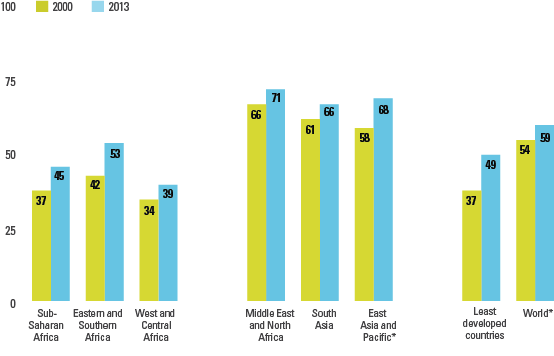

Annual child deaths from pneumonia decreased by 44 per cent from 2000 to 2013—from 1.7 million to 940,000 million—but many more lives could be saved.

Pneumonia and diarrhoea: Tackling the deadliest diseases for the world’s poorest children

This report makes a remarkable and compelling argument for tackling two of the leading killers of children under age 5: pneumonia and diarrhoea.

KEY TERMS

Acute respiratory infection (ARI): This includes any infection of the upper or lower respiratory system, as defined by the International Classification of Diseases. Acute lower respiratory infections (ALRI) affect the airways below the epiglottis and include severe infections, such as pneumonia.

Pneumonia: Pneumonia is a severe form of acute lower respiratory infection that specifically affects the lungs and accounts for a significant proportion of the ALRI disease burden. The lungs are composed of thousands of tubes (bronchi) that subdivide into smaller airways (bronchioles), which end in small sacs (alveoli). The alveoli contain capillaries where oxygen is added to the blood and carbon dioxide is removed. With pneumonia, pus and fluid fill the alveoli in one or both lungs, and this interferes with oxygen absorption, making breathing difficult.

Symptoms of pneumonia: Signs of pneumonia are a combination of respiratory symptoms, including ‘cough and fast or difficult breathing due to a chest-related problem’. Children exhibiting such symptoms should be taken to a health provider for a clinical assessment for pneumonia. Not all children with symptoms of pneumonia should receive antibiotic treatment; only children with a confirmed case of pneumonia (classified as such by the Integrated Management of Child Illness guidelines and based on a rapid respiratory rate counted by a health worker) should receive them. Current pneumonia-related interventions at the population level are measured through household surveys. However, evidence indicates that it is not possible to measure pneumonia prevalence among children under age 5 during a household survey interview or to ascertain underlying pneumonia for children with these respiratory symptoms.

Measurement limitations: Data collected through national household surveys, such as Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) and Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), report on the prevalence of symptoms of pneumonia, based on information about whether children have experienced coughing and fast or difficult breathing (due to a problem in the chest) in the two weeks prior to the survey. These children have not necessarily been medically diagnosed, and thus these data should be interpreted with caution. This limitation affects the accurate measurement of the coverage indicator on treatment of symptoms of pneumonia with antibiotics. The indicator becomes underestimated due to inflation of the denominators with children with apparent symptoms of pneumonia, but who did not actually have pneumonia, and therefore were not treated with antibiotics.